For the last 400 years, museums have offered a way for people to experience treasures from across the globe, as Margaret Powling explores

The earliest illustration of a natural history 'cabinet of curiosities', from 1599

This question is something of a rhetorical one: what do you do when you have bought a 27-ton railway engine? Richard Cuming, a railway enthusiast, purchased such an engine from Falmouth Docks in 1986. As luck would have it, an old cinema in his village came up for sale and so he and his family decided to combine their interests in railways and antiques and Bygones, a private family-run museum (www.bygones.co.uk), was born.

As Christine Garwood, a senior lecturer in Public History at the University of Hertfordshire, says, "From Liskeard to London, museums have become a key feature of the British cultural landscape, representing a host of subjects and passions developed by people and communities over time. With topics ranging from fans to football, museums can be found in almost every conceivable location – village or town, abandoned church or even disused sardine factory, reflecting our fundamental desire to 'collect, safeguard and make accessible artefacts and specimens'." (Museums Association, 1998)

My own first memory of visiting a museum is around the age of eight or nine when I was taken to Torquay Museum (www.torquaymuseum.org). Through the vaulted hall I went, up the stone staircase to the echo of our footsteps, and into a room filled with animals, albeit 'stuffed' ones. Like most children then, I had been instructed to look with my eyes, not my hands, because the items were not playthings; they were old, many of them fragile and of value, not necessarily of monetary value, but because of their historical merit.

And look I did. I looked in wonder at the mammals, reptiles and birds in their tableaux vivants; at the luminescent wings of butterflies and moths, and at a Narwhal 'tusk' like a giant's carved walking stick. Fast forward half a century and museums are still as popular as in my childhood. Furthermore, their visitors often feel protective of their exhibits; consider the fuss some of them made when they learned that Dippy, the dinosaur in London's Natural History Museum, was about to be replaced by the skeleton of a blue whale. And in recent months there has been a television programme, The Quizeum, in which experts visited a different museum each week and discussed artefacts in much the same way as in Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? during the 1950s.

Museums as we know them today often began as private collections with objects being housed in what are now referred to as 'cabinets of curiosity'. "The actual practice of collecting dates back to the oldest civilisations… to Babylon and the private collections of rare or curious natural objects and artefacts such as Ennigaldi Nanna's museum of Mesopotamian antiquities dating from c530 BCE," says Christine Garwood. "But while the practice of collecting is age-old, the word 'museum' [from the Greek and meaning a place or shrine dedicated to the Muses] was not used in English to mean a collection or building to display objects until the mid-17th century, when it was applied to botanist and gardener John Tradescant (c1570-1638) and son's dazzling 'collection of rarities', which by various twists became the basis of the University of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum [www.ashmolean.org]…which opened in 1683, and is the oldest surviving purpose-built museum in the world."

The Garden Museum (www.gardenmuseum.org.uk) was set up in 1977 in order to rescue from demolition the abandoned ancient church of St Mary's, Lambeth. It just so happens that this church is the burial place of the said John Tradescant, the first great gardener and plant-hunter in British history. His magnificent and enigmatic tomb is the centrepiece of a knot garden planted with the flowers which grew in his London garden four centuries ago.

It wasn't until 1660 that Britain saw the opening of the first public museum, the Royal Armouries in the Tower of London. The collection was originally created after the death of Henry VIII when the contents of several royal armouries were removed to the Tower where privileged visitors could view them privately. It was opened to the public during the reign of Charles II and, by the time of Queen Victoria's reign, the principle of the public museum was well established, many becoming national institutions with iconic buildings. Foremost architect of his day and designer of the Bank of England (demolished during the 1920s) and the Dulwich Picture Gallery, Sir John Soane (1753-1837) made his London home – where he lived with his wife and their two sons – a public museum (www.soane.org) instead of designing a separate museum for his collections. He began by buying number 12 Lincoln's Inn Fields in 1794 and gradually, over a period of 30 years, bought the two adjacent properties. He subsequently demolished all three and rebuilt, his home becoming a proving ground for new ideas in architecture and construction. Recently, Soane's private apartments (which haven't been on public view for 160 years) have been restored.

Fortunately for us, Soane was meticulous about keeping records, so the rooms have been replicated in precise detail, from the wallpaper to how they were arranged. Indeed, he was an imaginative designer of interiors and ingeniously constructed a system of hinged panels which opened out over one another to display Hogarth's The Rake's Progress. It is Prince Albert we must thank for some of our greatest museums. A devotee of science, education and the arts, he intervened in the debate about how the profits of £186,000 from the Great Exhibition of 1851 should be used, and these were combined with a £150,000 government grant to purchase 87 acres of land south of Hyde Park, an area subsequently referred to as 'Albertopolis'. Here were planned museums, colleges, and leading societies.

"Developments at South Kensington were mirrored across Britain by a network of municipal museums, an outgrowth of more fundamental developments such as industrialisation, education and the rise of the Victorian city and town," says Christine Gardwood. "Further momentum to the museum movement, and indeed free entry, was provided by sweeping concerns about the condition of the working classes. In this light, museums were seen as a form of 'rational recreation', a civilising influence and a meaningful distraction from less respectable pursuits such as the music hall and the pub." So not only were museums a repository of things which had hitherto been displayed in cabinets of curiosity, but they were also a useful tool in educating and even reforming the British public.

The desire to educate and to engage their audiences was instrumental in how museums created their displays, with greater attention now being paid to historical context rather than simply relying upon the assumption that visitors would have the ability to interpret large collections for themselves.

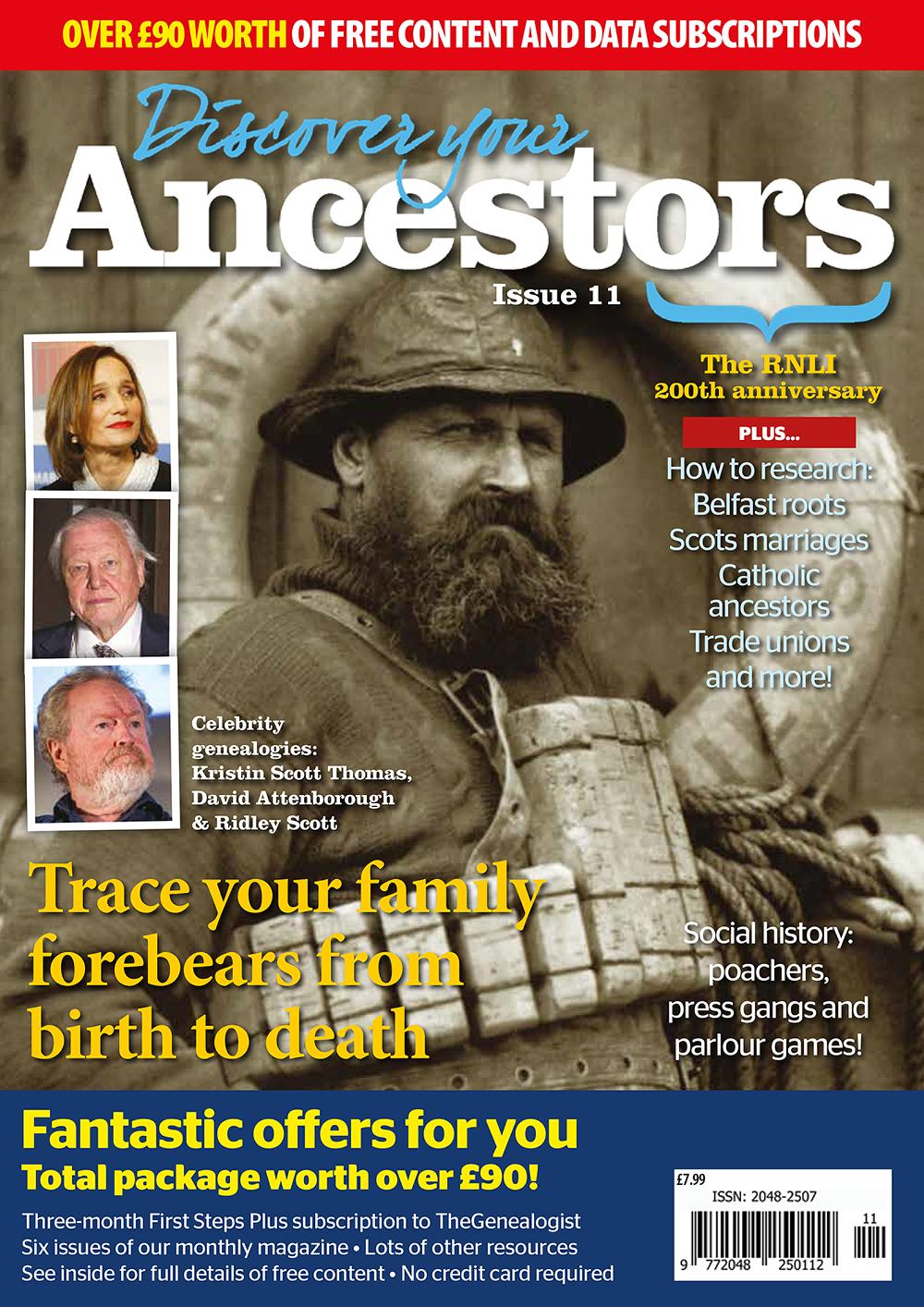

The Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London, as shown in the Illustrated London News in 1845

Today, the world of museums is as diverse as never before: from Beamish open-air museum in County Durham (www.beamish.org.uk) to the British Lawnmower Museum in Southport, Lancashire (www.lawnmowerworld.co.uk); from Charles Dickens Museum, 48 Doughty Street, London (www.dickensmuseum.com) to the Foundling Museum, the nation's first public art gallery and part of the old Foundling Hospital for abandoned children (www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk).

For me, perhaps the most romantic of all is the Bowes Museum (www.thebowesmuseum.org.uk) in Barnard Castle. It was purpose built in the French chateau style by John and Josephine Bowes to house their vast collections of fine and decorative arts. As the building grew, so did their collection; an astounding 15,000 objects were purchased between 1862 and 1874 and include a world-famous silver swan automaton. When Josephine died in 1874, John's motivation towards their lifelong achievement was dealt an enormous blow and he virtually ceased collecting. Fortunately, the building continued, but John, like his late wife, never saw its completion. He died in 1885.

A recent article in a national newspaper proclaimed that "boring museums are ancient history". Today, children are encouraged to dress up as Vikings or make fake dinosaurs. Terms such as 'interactive' and 'hands-on' are bandied about, and I fear that some museums are now in danger of becoming historical amusement arcades. But if children learn about the past by donning plastic helmets or cutting out cardboard stegosauruses, then so be it. I know which type of museum I prefer!

From our September 2015 issue (full contents here)

Subscribe Now!

Issue 11 of the critically acclaimed annual printed magazine Discover Your Ancestors is now available, featuring more than 140 pages of beautifully illustrated content to move your family history research on at pace. Read stunning features about life in the past, celebrity genealogies, Belfast roots, Scots marriages, trade unions, Catholic ancestors, and much more including and much more, delivered straight to your door.

Issue 11 is now available at this website and at more than 4,000 newsagents worldwide including WHSmith in the UK, Barnes & Noble in the USA and Chapters in Canada. While stocks last you can also purchase copies of back issues direct from this website.

Order Your Copy Today!You will be taken to our partner site GenealogySupplies.com to complete your order.