On 8 October, a Sunday, the people of Beverley were disturbed by the ominous sound of the town's common bell.

Some will have understood the meaning from previous ringings. Others will have recalled that, a few days earlier, they had seen the beacons fired on the southern horizon in nearby Lincolnshire, and will have connected the dots. Others still will have heard rumours of an uprising around Louth, and that 40,000 men were in arms to defend the churches of Lincolnshire.

Bells were a common way of transmitting alarm. Market bells, town bells, and church bells could all be rung in particular ways – usually with a rising pitch – to warn people to arm themselves, and to come out to muster. If an area was to raise itself – for the King, or against him – it depended on local worthies, the men who controlled the bells, to give the signal. In Yorkshire, in 1536, it was the call of rebellion that was heard.

Within a few weeks, a huge rebel army had amassed. It took Pontefract, the key to the North. The royal force sent to challenge it was pitifully small, and stood little chance in any straightforward military clash. It was a major insurgency: a serious problem for the government of King Henry VIII.

The rebels adopted the title of 'Pilgrims'. They protested the religious changes that Henry's government had unleased in the last few years, particularly the dissolution of the monasteries. But they also complained of economic malaise, and the influence of low-born men such as Thomas Cromwell. The rebellion attracted noble support, perhaps through coercion, but it was really driven by a one-eyed barrister called Robert Aske. York had fallen; there were rumours of a Spanish invasion. It was a desperate time for Henry.

Population growth

The Pilgrimage of Grace was probably the gravest threat the Tudor state ever faced, at least give or take the odd Armada (of these there were actually three). It was only faced down thanks to an astonishing deception by Henry VIII, promising the world to Robert Aske, even inviting him to spend Christmas with the royals, and then having him executed when rebellion started to brew again.

But it was not the only one. In fact, it's actually something of a miracle that the Tudor state survived at all.

It faced an astonishing set of challenges: inflation, enclosure, the squeezing out of small farmers, and industrial dislocation. It was a time of dangerous population growth – something we know about because we can count up the numbers of baptisms in parish registers. This put pressure on land, on wages, and on food supplies. It contributed to a growing poverty problem that was only partly dealt with by the newly-created poor laws. One of the upshots was famine: in the 1550s people starved to death, even in Westminster, and there were further famines in the 1587-8 and the late 1590s, particularly savage – this time – in the North.

And there were the problems of the government's own making. In the early years the Tudor dynasty had only the shakiest legitimacy, based as it was on the usurpation of the throne of Richard III by Henry VII. Henry's younger son, who became Henry VIII, then made things even harder by engaging in a series of expensive wars (which meant higher taxes), and – most controversial of all – by unilaterally withdrawing from the western Catholic church, reforming the liturgy in ways few desired, and pulling down England's glorious medieval monasteries.

Religion was to be a running sore for the Tudor regime for the rest of its days. The relative certainty of medieval faith had given way to plurality. Evangelicals, conservatives, Genevans, Romists, Church Papists, Jesuits, and eventually Puritans, and even radical new sects such as Baptists and Brownists all vied for influence.

Perhaps this would all have been less serious had the Tudor state been more powerful. But, in a technical sense, it was extremely weak. It had no police force worth the name, nor a standing army. Its bureaucracy was pitifully weak. As a result, it depended on the co-operation and administrative input of thousands of amateurs, men (and it was usually men) of often quite middling status including some of the wealthier peasants and tradesmen. These were the people charged with collecting taxes, putting statute law into practice, and dealing with crime and criminals. They served as justices of the peace (if they were of gentry status), or churchwardens, constables, and jurymen if they were peasants or villagers. They were satirized by Shakespeare in the character of Dogberry, but overall it seems they were surprisingly effective, even if they remained a potentially very thin line in the face of social unrest.

Social unrest

This social unrest was a constant problem. Even after the failure of the Pilgrimage, the spectre of serious rebellion would continue to haunt the Tudor state.

There was another major uprising against a new Protestant Prayer Book in the conservative West Country in 1549, which was bloodily repressed. And the Pilgrimage itself had something of a sequel in the north in 1569-70, when a rebellion by two Catholic northern earls actually drew considerable popular support. There was also, during the reign of the Catholic Mary I, a rebellion in Kent under the leadership of Sir Thomas Wyatt and three other prominent Protestants.

Other revolts centred on unpopular taxation. In 1497, a serious insurgency in Cornwall had seen a rebel army push to the outskirts of London to protest having to pay towards a war against distant Scotland. The repression was brutal. Then in 1525, in one of the few successful uprisings of the age, a gathering against an unpopular (and ironically named) tax called the 'Amicable Grant' forced Henry VIII's government into an embarrassing retreat. The King's main advisor, Cardinal Wolsey was forced to apologise, the rebels were pardoned, and the tax was quietly dropped.

Many of the issues behind popular rebellions – enclosure, rising rents, squeezed incomes – were felt across wide swathes of the country, and as Robert Kett's rebels (see box above) demanded redress from their camp in Norfolk, many other, smaller camps were formed across the country. They pulled down hedges, and attacked deer parks. So widespread were the disturbances that the year came to be known as the 'Camping Time', or simply the 'Commotion Time'.

But as 1549, and Kett, passed into memory, such large-scale disturbances became ever more rare, even as the economic problems worsened. In the 1590s, despite living standards dropping to perhaps their lowest ever level, and despite plague, war, and famine, there was no major rebellion. Apprentices rioted in London, and aristocrats plotted at court, but there was – it seems – no appetite for a major uprising. In 1596 one was planned, from farmhouses and taverns in northern Oxfordshire but, at the appointed date and the appointed time, only a handful of people turned up, and they were quickly mopped up by the authorities.

The lack of major uprisings after 1570 is all the more surprising because riot – the smaller cousin to rebellion – was a constant problem. High price years, such as the late 1550s, or 1586, brought food riots – especially in grain-growing regions such as Essex, which were forced to ship out their wheat and barley to hungry cities like London. Enclosure of common land was often resisted by rioting – with angry farmers pulling down the offending hedges and fences.

But, as the 16th century wore on, these localised outbreaks of disorder were increasingly unlikely to break into a full scale rebellion. Why was this?

Decline of rebellion

One set of reasons is probably that the Tudor state was increasingly secure at the top. One of Queen Elizabeth's main achievements was that she managed to live long enough to both outlast any dynastic rivals (the main one, Mary Queen of Scots was executed by Elizabeth's government in 1587), and to allow Anglicanism, unlike Edward IV's Protestantism or Mary's Catholicism, the time to put down solid roots. So the dynastic and religious uncertainties that had beset the monarchy in the 15th and early 16th centuries were drastically lessened.

There were also new government institutions that might have helped hold back the call of rebellion. A new, more effective, militia was created under Elizabeth, and this would undoubtedly have been able to react more quickly to disturbances. The Tudor poor laws, meanwhile, might have eased the pressure on the most vulnerable and disaffected (though it tended to target the old and the sick, who were unlikely rebels). There was also a growth in litigation, and increasing use of the many and various English law courts, some of which – such as the courts of Chancery and Exchequer Chamber – seem to have been especially willing to give dispossessed peasants a fair hearing.

But perhaps the most interesting theory relates to those men who served in government offices: the Dogberries. For the economic changes of the 16th century had both winners and losers, and if you were of middling status – maybe a relatively wealthy peasant with a secure lease on your land – then you were one of the winners. Among these winners, the English 'yeomen', farmers who were wealthy and secure but still below the ranks of the gentry, were especially prosperous, so much so that many of them rebuilt their farmhouses, giving us many of the elegant vernacular Tudor buildings that survive in today's countryside.

As they got wealthier, these yeomen tended to see their interests align more and more with the social order, and less with their poorer neighbours. They benefited from enclosure, and high prices. If they were leasing out their land they also benefited from rising rents. But it was not just economic selfinterest that drove them away from rebellion. They were also more likely to read books, to attend schools and universities, perhaps even to embrace puritanism. They were, in a real sense, becoming part of the rural 'establishment'.

So, by 1600, when rebels came knocking, it was more likely that market halls and church towers would remain closed, their bells unrung.

From our October 2015 issue (full contents here)

DR JONATHAN HEALEY teaches early modern history at the University of Oxford, where he is a Fellow of Kellogg College. His research focuses on the English poor and peasantry, and his first book The First Century of Welfare: Poverty and Poor Relief in Lancashire, c1620-1730 came out in 2014. He runs Oxford University's Advanced Diploma in Local History (Online), which is open to all – see www.conted.ox.ac.uk/V321-13.

Subscribe Now!

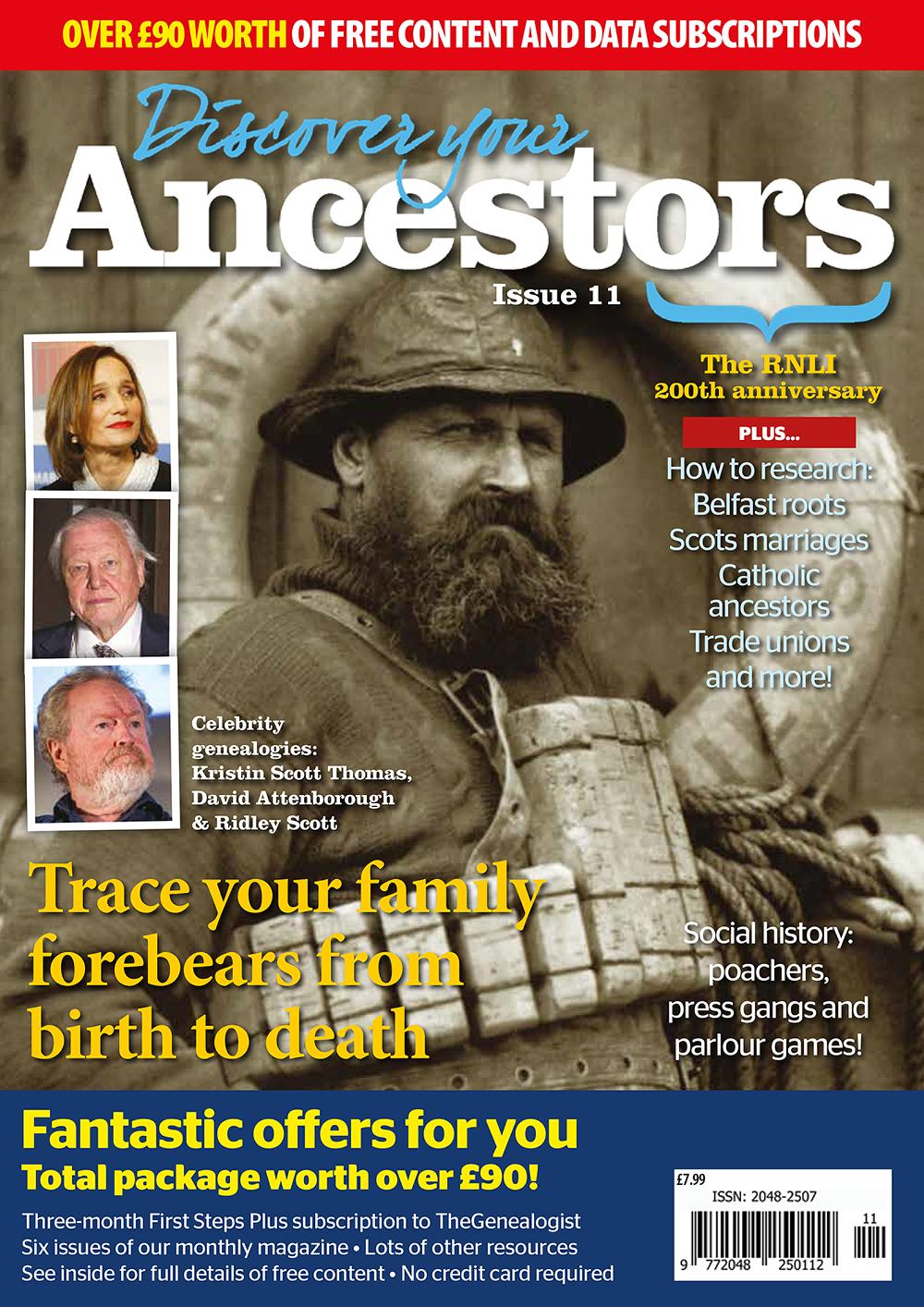

Issue 11 of the critically acclaimed annual printed magazine Discover Your Ancestors is now available, featuring more than 140 pages of beautifully illustrated content to move your family history research on at pace. Read stunning features about life in the past, celebrity genealogies, Belfast roots, Scots marriages, trade unions, Catholic ancestors, and much more including and much more, delivered straight to your door.

Issue 11 is now available at this website and at more than 4,000 newsagents worldwide including WHSmith in the UK, Barnes & Noble in the USA and Chapters in Canada. While stocks last you can also purchase copies of back issues direct from this website.

Order Your Copy Today!You will be taken to our partner site GenealogySupplies.com to complete your order.