Family historian Chris Paton explains the judicial role of the kirk session in Scotland...

Although Scottish parish registers helpfully allow us to trace who our ancestors were, it is the records of the kirk sessions that more specifically help us to understand how the Kirk worked within society as an institution. The registers of individual kirk sessions not only recall the everyday administrations of a church''s elders and minister, but also provide a record for one of the session''s primary functions – its role as the lowest of the Kirk''s courts.

The Kirk, or Church of Scotland, underwent its Reformation in 1560, changing from a Roman Catholic-based institution to a Presbyterian-based religion. At the heart of the new faith was an idea that John Knox had appropriated from the Swiss reformer John Calvin – the concept of a 'Godly Commonwealth'' at the very heart of Scottish society. This essentially stated that the Church was to be responsible for the moral discipline and education of its flock, working in partnership with the state. In its earliest 'Calvinist'' form, the new Presbyterian Kirk preached to its congregations that its members were all damned to hell unless they had been predestined to join God in the afterlife as one of a chosen 'Elect''. As nobody knew who the chosen elite were, everyone was encouraged to aspire to the values expected of the Elect. Education of the flock would lead to an understanding of 'godliness'', while discipline would see it fulfilled. In time the theology would mellow, but it would not be until the 19th century that the Kirk finally relegated its role of disciplinarian to the state.

Each parish had its own kirk session, consisting of the kirk''s elders and minister, which would hear cases of breaches of church discipline. Among the offences that could be investigated and punished were participation in irregular marriage, antenuptial fornication, profanity, drunkenness, disrespecting the Sabbath, defamation, domestic violence, infanticide, abortion, and even witchcraft. If any decisions and punishments of the session were ignored by the guilty party, the session could call on the local Justice of the Peace for support to help implement a sentence, or refer a case to the burgh court if within a royal burgh. A parishioner wishing to appeal against a judgement by the session could do so through the higher court of the presbytery to which the parish formed a part – the presbytery would also hear cases in the first instance where an offence may have been carried out by parishioners from two separate parishes. Cases could be further referred higher still to the court of the synod, and ultimately (rarely) to the General Assembly.

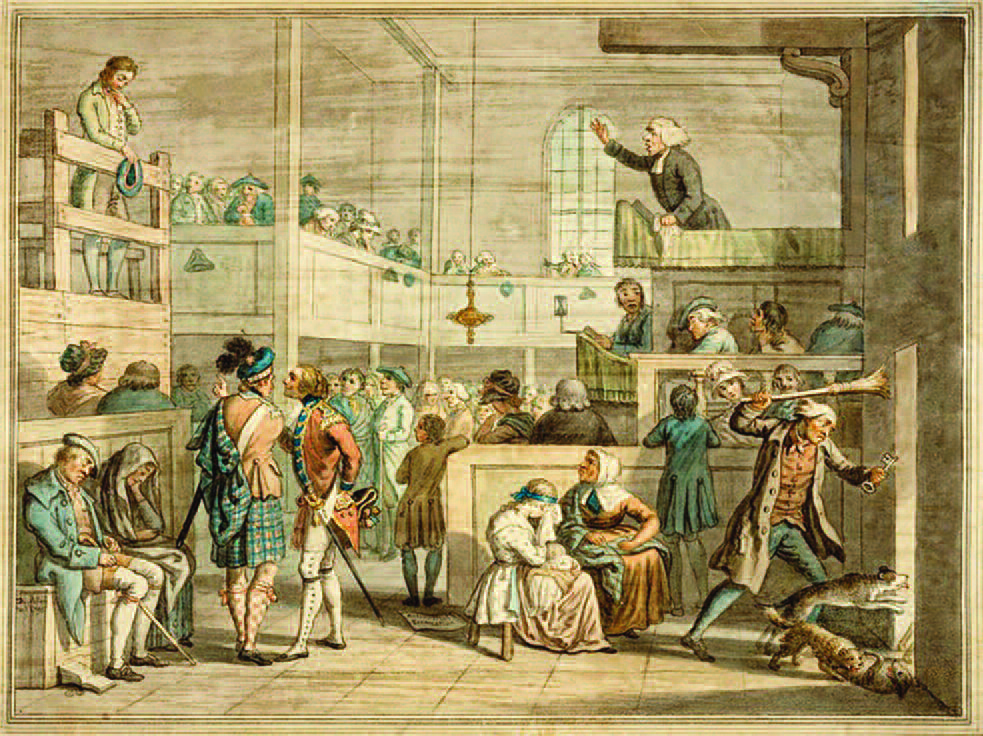

Once convicted, an offender could be punished in a variety of ways. From the 16th to the late 18th centuries, it was common for the convicted person to be publicly humiliated by being made to wear sackcloth, and to sit on a penitent''s stool in front of the congregation. It would not be until the early 1800s that rebukes would be performed in private, in front of the session alone. Church privileges could also be removed, such as the right to attend service, to have children baptised, and more.

The most common offences were antenuptial fornication, adultery and the births of illegitimate children following 'scandalous carriage''. In such cases the kirk session would haul the accused couple before them to admit the 'sin'' and 'scandal'' of the offence committed. If they did so, they would be fined and rebuked, often on several visits to the session or in front of the congregation, before being absolved. A formalised Act from 1707 outlining the procedures involved is laid out in Acts of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland 1638-1842 (available via Google Books at http://bit.ly/1wp6vJw).

During the course of an enquiry it was not uncommon for a pregnant woman to be visited by an elder in the midst of labour and exhorted to confess the identity of the father, if she had previously refused to name him. If a woman was accused of having recently given birth, and denied the claim, the session could order one of its elders to milk her breasts and, if milk was produced, to use that as evidence against her of guilt. Even in circumstances where a woman claimed to have been raped, the session was instructed to investigate her moral character and former behaviour, and she was to be 'seriously dealt with to be ingenuous''.

At times, cases would result in deadlock, with neither the woman or the man involved in an accusation refusing to budge on their conflicting evidence. In such cases, the putative father could be offered the chance to give an 'oath of purgation'' before the kirk session, presbytery or congregation. This was a solemn oath made before God expressing his innocence, after which he would be absolved of the scandal, as judgement would then have been passed to the highest authority. In cases where an illegitimate child had been produced, failure to give the oath by the father, once demanded, could lead to his excommunication. The mother would again be challenged after such an oath had been given and, if still accusing the putative father of his role, she could be heavily censured

On the darker side, within kirk session records you can also find records testifying to the hysteria within a parish, or the misuse of the session to try to slander others. In particular, before 1736 there were many allegations of witchcraft found within the registers.The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft (www.shc.ed.ac.uk/Research/witches) is an online database which has details of nearly 4000 people who were tried from 1563-1736 for allegedly dabbling in the dark arts. Although the kirk sessions could not prosecute suspects for what was a criminal offence, they did interrogate suspects before passing on the allegations to the criminal courts. If found guilty, supposed witches could be banished, excommunicated, or even executed. Some parishioners deliberately sought to use witchcraft as a malicious means of slander, but if found out they could be punished themselves.

By the 19th century, as a result of the industrial and agricultural revolutions, the Kirk was beginning to lose its grip and influence on society. As an institution it saw many schisms, with congregations walking away to form new denominations on disputed points of doctrine. These new bodies continued to hold their own sessions, but no longer being part of the established church they did not have the means to refer many of their cases to the civil authorities. The emergence of police forces finally put paid to any influence on discipline by the Kirk, the role being largely transferred to the state.

Most kirk session records are accessible in a digitised format at the National Records of Scotland (www.nrscotland.gov.uk). Some have also been returned to local county archives, while several remain in private hands. For some parishes records have been indexed or transcribed and published – for example, indexes to kirk session records from several Dumfries based churches have been made available at http://info.dumgal.gov.uk/HistoricalIndexes/.

No matter how innocent your ancestors'' lives may appear to have been from the vital records registers, the kirk session registers are always worth consulting. Your ancestors or their neighbours may well have appeared as witnesses in cases – and you never know, they may well have been in the dock themselves.

Read Chris's article about free websites for researching Scottish roots in Issue 4 of Discover Your Ancestors (available to purchase here)

CHRIS PATON holds a postgraduate diploma in Genealogical Studies from the University of Strathclyde and runs the Scotland's Greatest Story family history research service (www.scotlandsgreateststory.co.uk). He is the author of Down and Out in Scotland: Researching Ancestral Crisis (2015, Unlock the Past), Discover Scottish Church Records (2011, Unlock the Past), Tracing Your Family History on the Internet 2nd ed. (2014, Pen and Sword), and Researching Scottish Family History (2010, Family History Partnership).

Subscribe Now!

Issue 11 of the critically acclaimed annual printed magazine Discover Your Ancestors is now available, featuring more than 140 pages of beautifully illustrated content to move your family history research on at pace. Read stunning features about life in the past, celebrity genealogies, Belfast roots, Scots marriages, trade unions, Catholic ancestors, and much more, delivered straight to your door.

Issue 11 is now available at this website and at more than 4,000 newsagents worldwide including WHSmith in the UK, Barnes & Noble in the USA and Chapters in Canada. While stocks last you can also purchase copies of back issues direct from this website.

Order Your Copy Today!You will be taken to our partner site GenealogySupplies.com to complete your order.