Angela Buckley reveals how you can track down your criminal ancestors – assuming they were caught

All families have skeletons in their genealogical closets and finding a criminal ancestor adds colour to a family tree; even the most 'respectable' families have secrets lurking just under the surface. Many factors can drive an individual to commit a crime and, if your ancestors were struggling to survive, then they may well have strayed over to the wrong side of the law. In the 19th century, extreme poverty, without the safety net of state assistance, was intrinsically linked to criminal acts, as well as other more complex reasons such as mental health issues.

The most common crimes in the 1800s were theft and assault. Other indictable offences included burglary, breach of the peace and drunkenness. Drink-related crimes were high due to the widespread availability and excessive consumption of alcohol.

Struggle for survival

Life was tough in the developing urban landscape of the Victorian era. In the wake of the Industrial Revolution thousands of migrant workers poured into cities to seek employment in factories and mills. In Manchester, the number of inhabitants rose from 76,788 in 1801 to 316,213 in 1851. The crime rate increased exponentially and, by 1870, it was 1.86 per capita, which was four times higher than in London.

Throughout the country workers lived in deplorable conditions: cramped tenements with no running water, ventilation nor amenities. The wages were barely adequate to feed a family so many turned to petty crime to supplement their income. Theft of clothing was particularly prevalent and people were so desperate that they even stole from washing lines.

Even though crime is often associated with cities, rural communities had their fair share of illicit acts, the most common being poaching, theft of livestock, cruelty to animals, larceny and drunkenness. By the mid-19th century, the farming industry was in decline due to economic depression, political changes and the development of new technology. Agricultural labourers had already been affected by enclosure, which had limited the land available for growing food and grazing animals. The introduction of threshing machines in the early 1830s posed a major threat to their livelihood and many unskilled workers were forced to move to the towns.

Regardless of whether your ancestors lived in the newly emerging cities or remained in the countryside, many of them would have lived a hand-to-mouth existence. Unemployment was high and, for those in work, wages were often low. When the Poor Law Amendment Act abolished outdoor parish relief in 1834, families faced the prospect of the dreaded workhouse and its harsh regime. Furthermore, the chances of breaking the law became even higher due to an increase in legislation. Many activities were criminalised, such as animal sports, gambling and the unlicensed sale of alcohol, as new offences were added to the statute book throughout the century. The likelihood of being caught increased too with the introduction of an organised police force.

Prior to the creation of the new police by Sir Robert Peel in 1829, communities had been responsible for their own policing. Parishes and townships relied on a local constable and night watchmen to protect inhabitants. Identification of suspects was dependent on local knowledge and offenders were often handed over by their neighbours, and sometimes even their families. My 2x-great-uncle, Cornelius Willoughby, a farm labourer from West Overton in Wiltshire, was shopped by his stepmother in 1844 for stealing potatoes belonging to a local publican. He was sentenced to six weeks' penal servitude. This type of crime and the ensuing arrest was commonplace at the time. As more regional police forces were established, suspects were more likely to be arrested by the local 'bobby'.

Caught in the act

Individuals apprehended on suspicion of breaking the law were charged and initially brought before a local court. Minor offences, such as drunkenness and swearing, were usually tried at the Petty Sessions. These were summary courts with two presiding magistrates and no jury. The magistrates were upstanding members of the community, often landowners, which could have grave consequences for offenders caught poaching on their property. Towards the end of the 19th century, police courts took over their work.

More serious offences, like theft and wilful damage, were tried at the Quarter Sessions. They were held four times a year and comprised a jury and justices of the peace. For the worst crimes, such as murder, defendants were tried at the Assizes, which were presided over by two or more judges who travelled a circuit throughout the country. Both Quarter sessions and Assize courts were replaced by the crown courts in 1971. (You can read more about the three court tiers in the October, November and December 2013 issues of Discover Your Ancestors Periodical.)

There was a wide range of punishments for dealing with convicted criminals, from a fine or short prison sentence for petty offences, to the ultimate sanction of the death penalty. By the early 19th century, the list of capital offences had been reduced and the punishment for many lesser crimes had been commuted to imprisonment. At the same time, the prison system was evolving, with local houses of correction being gradually replaced by large penitentiaries. These institutions provide a wealth of material for family historians.

Transportation was re-introduced in 1787 due to overcrowding in mainland prisons so you may discover a convict ancestor sent to the penal colonies, or housed in one of the prison hulks, which were decommissioned wooden ships initially moored in the river Thames. As penal reform continued, transportation ended in 1853, with the last convicts leaving British shores in 1867. (For more on transportation, see the February and March 2015 issues of Discover Your Ancestors Periodical.)

Criminal records

Meticulous Victorian record keeping makes it possible to track individuals through the complex criminal justice system and, once you have discovered a family felon, you can follow the progress of the court procedure through the criminal records, working through each stage until you reach a conclusion. A good starting point for locating a criminal ancestor is the 'calendar of prisoners'. These lists were published before trials and contain basic information about the alleged offence and personal details of the prisoner. They are available in county record offices and at The National Archives.

County record offices are vital to finding out more about individuals who broke the law. They hold records for Petty and Quarter Sessions, as well as other supporting documentation, for example, calendars of prisoners, depositions, recognisance bonds and coroners' reports. Many of these documents are not available online but record offices have online indexes and copies can be ordered through some websites. The online collection at TheGenealogist.co.uk includes early county court records for Worcestershire and constables' accounts for Manchester. Some local family history societies publish indexes and transcriptions for pre-19th century trials.

The most comprehensive collection of criminal records is held at The National Archives in Kew, comprising convict records, warrant books, calendars of prisoners, prison registers and assize records. Their online research guides give detailed information about the different categories of records available. Many TNA records can be accessed at TheGenealogist.co.uk, including convict transportation registers, criminal registers and pardons. Transcripts of Old Bailey trials, from 1674 to 1913, can be downloaded from www.oldbaileyonline.org.

By following the trail through the courts, you will discover information about a convicted criminal's circumstances, as well as their crime. Prison registers hold fascinating details for family historians about the individuals recorded, including physical descriptions and personal information. For example, my ancestor John Dawson was convicted of “keeping a disorderly house” in Manchester in 1868. The Belle Vue prison register describes him as having a sallow complexion with teeth missing from his upper jaw, and one of his fingers had been cut off from his right hand. It is also important to explore other related records, such as those from asylums, industrial and reformatory schools and workhouse records, as these will all help to build a picture of your law-breaking ancestor and give you hints as to why they turned to crime.

Another invaluable resource is contemporary newspapers. Victorian newspapers reported crime in great detail, from minor offences to the most sensational trials of the era. They recorded court proceedings and followed every stage of the judicial process, usually in colourful detail. It is often possible to find information in the local press that is unavailable elsewhere especially for inquests, as many coroners' reports have not survived. The Diamond subscription package at TheGenealogist.co.uk offers access to a range of publications, including the Illustrated London News.

Finding a criminal ancestor is always an exciting moment and, apart from learning about an individual's misdemeanours, it gives invaluable insight into how our ancestors lived and the challenges they faced in their daily life. Their stories can add intrigue and drama to your family tree and, once you get started, it won't be long before you hear the rattle of bones!

In the print edition

Read more about the Poor Law in Issue 4 of Discover Your Ancestors, out now in newsagents or available online at www.discoveryourancestors.co.uk

ANGELA BUCKLEY (www.angelabuckleywriter.com) writes about Victorian crime. She is the author of The Real Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Story of Jerome Caminada (Pen and Sword, 2014). She is chair of the Society of Genealogists.

From our April 2015 issue (full contents here)

ANGELA BUCKLEY (www.angelabuckleywriter.com) writes about Victorian crime. She is the author of The Real Sherlock Holmes: The Hidden Story of Jerome Caminada (Pen and Sword, 2014). She is chair of the Society of Genealogists.

In the print edition: Read more about the Poor Law in Issue 4 of Discover Your Ancestors, available to buy here.

Subscribe Now!

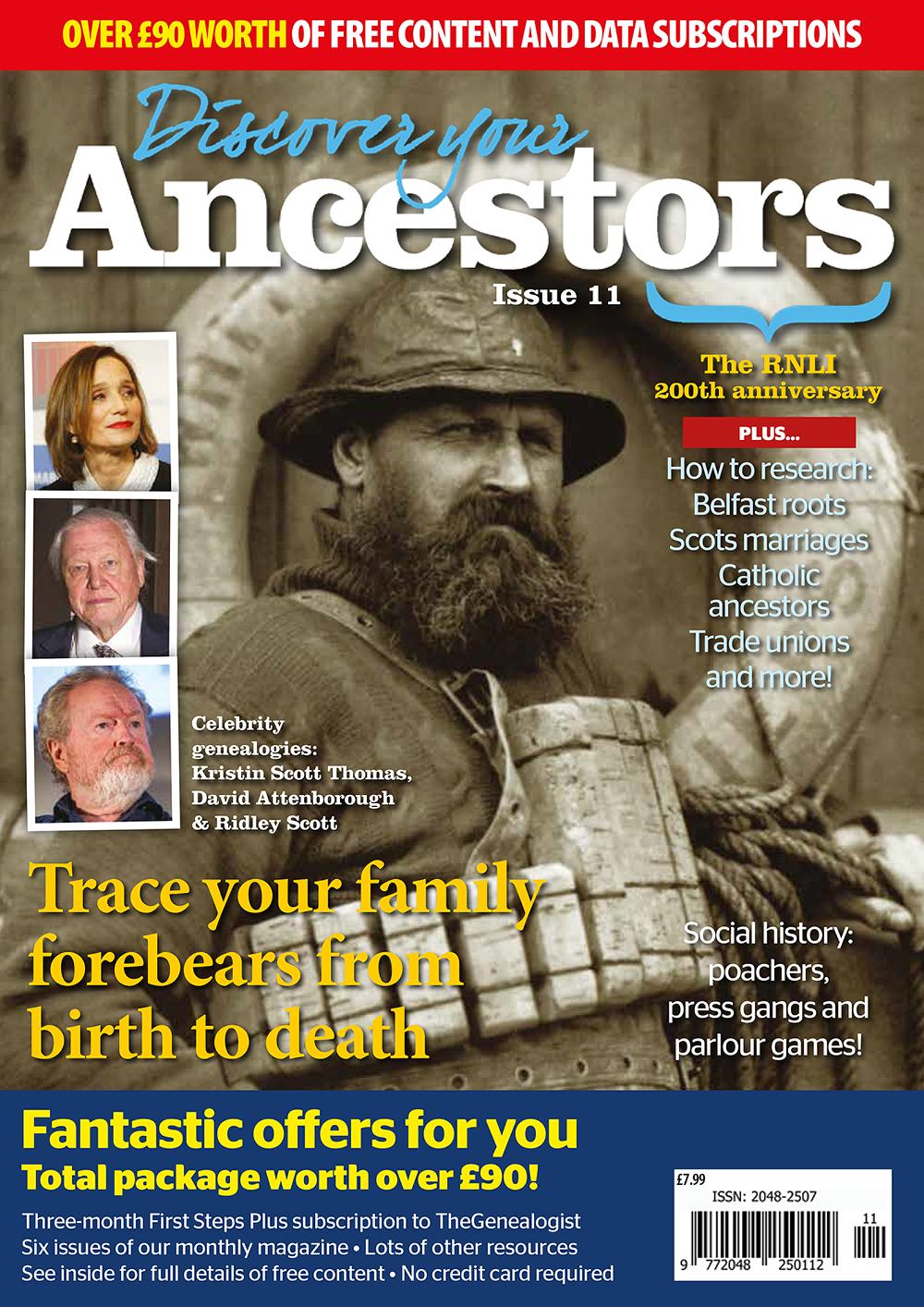

Issue 11 of the critically acclaimed annual printed magazine Discover Your Ancestors is now available, featuring more than 140 pages of beautifully illustrated content to move your family history research on at pace. Read stunning features about life in the past, celebrity genealogies, Belfast roots, Scots marriages, trade unions, Catholic ancestors, and much more, delivered straight to your door.

Issue 11 is now available at this website and at more than 4,000 newsagents worldwide including WHSmith in the UK, Barnes & Noble in the USA and Chapters in Canada. While stocks last you can also purchase copies of back issues direct from this website.

Order Your Copy Today!You will be taken to our partner site GenealogySupplies.com to complete your order.